Posted by By Julie Anderson October 2, 2022 on Oct 9th 2022

Heart disease deaths, down for decades, tick up in Nebraska, U.S.

Heart disease deaths, down for decades, tick up in Nebraska, U.S.

After Robert Burgess got out of the Nebraska Medical Center in late April after a near-fatal heart attack, he changed his lifestyle.

The 75-year-old from Shenandoah, Iowa, quit smoking and started checking the sodium and cholesterol content of the food he bought at the grocery store. He also cut out treats like doughnuts.

By early September, his heart tests looked good. A little more than four months after local first responders and a medical helicopter crew shocked his heart four times, his cholesterol was low and he had lost about 35 pounds. A few weeks ago, the retired metalworker graduated from a cardiac rehabilitation program at his local hospital.

“It was a life-changing experience,” Burgess said.

The number of heart disease-related deaths has declined for decades in the United States, a trend cardiologists attribute largely to the decline in smoking, the recognition and treatment of hypertension and high cholesterol and newer treatments such as those that saved Burgess.

Despite that remarkable shift, heart disease remains the nation’s leading cause of death. In Nebraska, heart disease trails cancer by a razor-thin margin as the leading life-taker. Between 2011 and 2020, cancer on average claimed just under 3,500 Nebraskans a year, roughly 50 more than the number who died each year from heart disease. In Iowa, however, heart disease remains the leading cause of mortality.

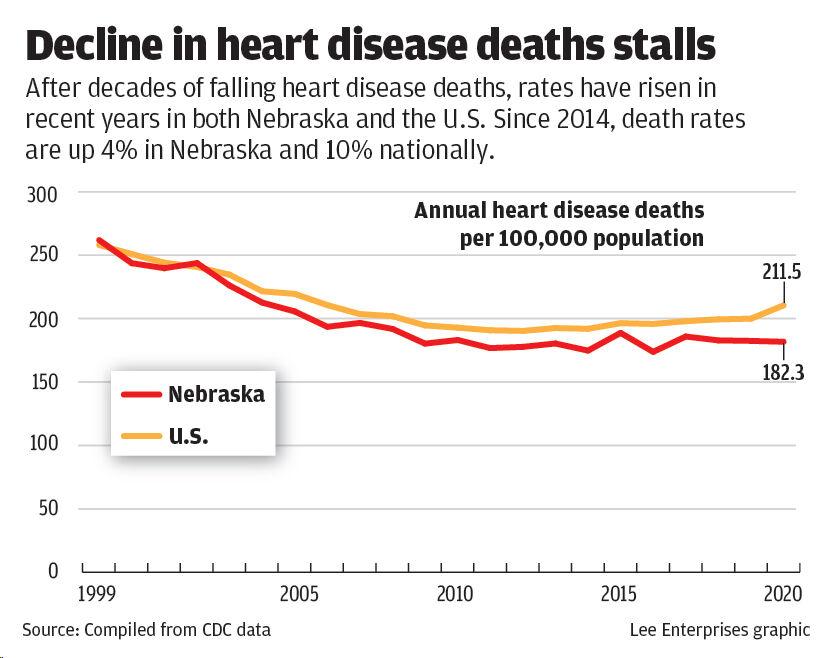

But after decades of declining numbers of heart disease-related deaths, rates have risen in recent years in both Nebraska and the U.S. Since 2014, heart disease-related death rates are up 4% in Nebraska and 10% nationally, according to a World-Herald analysis of data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Iowa, where Burgess lives, is among the states that have continuously seen more people die from heart disease than cancer. Heart disease-related deaths there have trended up 11% between 2014 and 2020.

Although there’s no definitive explanation why heart-related fatalities have plateaued and even ticked up, cardiologists cite a number of factors: the population is aging, obesity continues to rise and physical activity has declined.

“We haven’t reached the apex of that problem,” said Dr. Eric Van De Graaff, a cardiologist with CHI Health in Omaha. “I would suspect that the rate of deaths from heart disease has reached a low point and will be on the rise for a little while.”

On the flip side, said Dr. William Nester, an interventional cardiologist with Methodist Health System, the numbers haven’t risen drastically despite those trends because health care providers have a lot more targeted therapies that they can deploy to prevent patients from having poor outcomes.

“We’re capturing a lot of these patients earlier,” he said. “We’re doing primary prevention with them where we’re starting them on medication before an event happens.”

Dr. Andrew Goldsweig, medical director for structural heart disease at Nebraska Medicine, said the improvements in prevention, medical therapy and procedural treatments that have helped reduce the worst effects of heart disease over the decades now are becoming more incremental.

The treatments Goldsweig used on Burgess are the product of decades of development. Goldsweig, an interventional cardiologist, first threaded a tiny pump through an artery in Burgess’ leg. Once in the heart, the device temporarily took over the organ’s job. Through the same catheter, Goldsweig then used balloons and a stent to open Burgess’ blocked artery. After Burgess’ heart function improved, Goldsweig removed the pump.

“At this point, we’re having smaller advances,” Goldsweig said. “Our stent sizes are getting smaller, our procedures are getting less invasive, hospitalizations are getting shorter. ... But we’re not having any huge breakthroughs.”

* * *

One hundred years ago, infections — diseases of inadequate public health — claimed the lives of most Americans, said Van De Graaff, an assistant professor with Creighton University’s School of Medicine.

In 1900, the average life expectancy in the United States was 47 years.

Over the course of 50 years, that number improved. People started living long enough to die of heart problems, said Van De Graaff, noting that the percentage of cardiac-related deaths peaked in 1968.

Three things caused heart-related deaths to decline, he said, the single biggest factor being the decline in smoking. Nationally, cigarette smoking rates have declined 68% among adults, from 42.6% in 1965 to 13.7% in 2018, according to the American Lung Association.

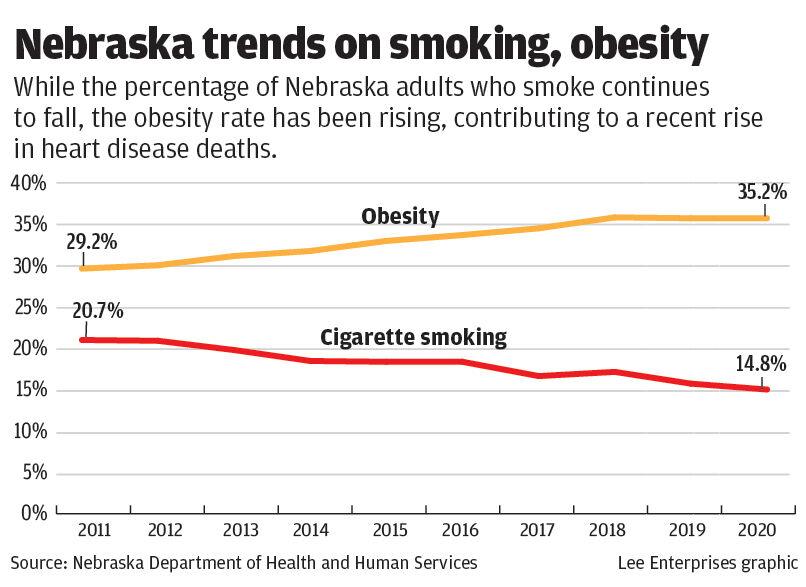

Between 2011 and 2020, the percentage of adult Nebraskans who smoked decreased from 20.7% to 14.8%, according to CDC data.

The figure was lower among youths, with 4.2% of high school students in 2019 reporting that they smoked, according to the CDC. A total of 18.8% of those students reported using any tobacco product, including e-cigarettes.

Next came the recognition and treatment of hypertension, Van De Graaff said. When he was in medical school, the doctors teaching him and his classmates told them that when they were in med school, they learned that a normal blood pressure reading was the patient’s age plus 100. But epidemiological studies in the 1970s determined that the ideal reading was 120/80. Treating to that level could cut down on strokes, kidney disease and heart attacks.

Third was the use of cholesterol medications, or statins, which came out in the early 1980s. While some refuse them, Van De Graaff said, they were the most studied class of medications until the COVID-19 vaccines. Those studies found that if people take a statin, they reduce their risk of heart attack by 30% and of stroke by 40%.

Those three factors, according to most large studies, account for 50% to 70% of the drop in heart-related deaths, he said. Deaths from cancer, too, have decreased, just not as quickly.

Today, the decline in deaths from heart disease also is leveling out, Van De Graaff said, and in some populations has begun to rise. The nation is seeing a new sort of heart disease resulting from sedentary lifestyles and an increase in obesity.

The number of Nebraska adults considered obese increased from 29.2% in 2011 to 35.2% in 2020, putting the state at No. 19 among states. Iowa, with 36.5% of adults considered obese, came in at No. 8.

That’s where things get complicated. Obesity itself doesn’t directly lead to blocked arteries, Van De Graaff said, but it can do so indirectly through a complex mix of mechanisms, the most significant of which are increasing the risk of Type 2 diabetes and sleep apnea.

When it comes to sleep apnea, the repetitive pauses in breathing that characterize the condition can stress and potentially damage not only the heart but also the entire cardiovascular system.

The most compelling theory explaining diabetes’ role in heart disease, Nester said, is that the higher blood sugars associated with the condition cause higher levels of inflammation in the body. Inflammation in the heart arteries narrows the structures and allows blockages to form. High cholesterol can add to them.

Physical activity also has declined among Americans. In Nebraska and Iowa, between 20% and 25% of adults surveyed reported being physically inactive, according to the latest maps from the CDC.

The good news, Van De Graaff said, is that evidence indicates even small changes in physical activity can improve cardiac health.

Nester advises people to start small, walking 20 minutes once a week. Once they can do that, he advises working up to three to five days a week.

“That has time and time again proven to be one of the best things you can do for your heart health,” he said of walking.

Nester said he and his dog, a Husky, cover about two miles in half an hour on their morning jaunts.

Goldsweig said 80% of cardiovascular disease, in fact, can be prevented by healthy lifestyle choices and risk factor management.

Awareness of the impact of lifestyle choices and the availability of healthy foods and exercise options, he said, have helped prevent bad outcomes.

On the other hand, difficulty accessing affordable, healthy foods and exercise opportunities can have the opposite effect on health, said Jamin Johnson, health equity adviser for the Douglas County Health Department.

Those factors and others that affect health, such as persistent economic disparities, are known as social determinants of health. Social determinants of health play into the higher rate of heart disease-related mortality among Black residents in Douglas County, which exceeds that of White residents and that of all residents combined, according to the county’s 2021 Community Health Needs Assessment.

The Douglas County Board of Health has prioritized addressing these underlying factors. Community gardens are one type of initiative that can work, Johnson said. Not only do they produce healthy foods, they also allow users to engage in moderate physical activity and build social connections.

Health officials also are working to partner more closely with churches and other faith-based groups that maintain food pantries so they can provide contacts for other supports, such as job and housing assistance, Johnson said. The county’s Women, Infants and Children services provide supplemental food and nutrition education to low-income mothers and young children.

Goldsweig said preventive measures such as regular screening and care are important in preventing heart disease-related deaths. Those deaths have gone down even as the incidence of cardiovascular disease itself has increased.

Because of the importance of access to primary care in providing screening and care, Johnson said, health officials are trying to make sure Douglas County residents know they can connect with providers regardless of their insurance status through Charles Drew Health Center and OneWorld Community Health Centers.

Prevention starts with detection, the routine monitoring of blood pressure and cholesterol levels. Further down the diagnosis chain are advanced cardiac imaging, including CT scans, MRIs and nuclear stress testing.

The number and type of treatments also has expanded. In addition to the cholesterol-lowering statins, Goldsweig said, doctors now have eight classes of blood pressure medicines and the ability to aggressively treat diabetes.

For heart attack sufferers such as Burgess, options include bypass surgeries and angioplasty, which involves using a tiny balloon to open blocked vessels from the inside.

Doctors started using angioplasty in 1978, Nester said. “That has been the biggest change in heart disease over the last 30 to 40 years, is that we can intervene and change the course of a heart attack,” he said.

Stents, the mesh tubes that can be used with angioplasty, have been around since the 1990s, followed by drug-coated stents in 2004, Goldsweig said.

Increased access to health insurance over the past decade also has helped more people get both medications and procedures when needed, he said.

In addition, many non-medical people have been trained to perform CPR and use automated external defibrillators to shock the heart of a person who’s in cardiac arrest. Goldsweig said it’s rare that he sees a heart attack patient who hasn’t had CPR. Bystanders gave Burgess CPR for 15 minutes.

In ambulances and hospitals, the timing of care delivery is broken down minute by minute. For instance, the time from when a heart attack patient arrives in an emergency room to the time a balloon is inflated in a blocked artery should total 90 minutes or less.

“It’s a different world where conditions that used to be fatal are handled very easily,” Goldsweig said. “And people have access to them all over.”

Burgess said he didn’t know what happened to him that April day until he woke up in the hospital and hospital staff told him he’d had a heart attack. He’s back to his normal activities, including mowing his lawn, with no problems.

“I’m doing well now,” he said.