AHA BLS For Healthcare Providers Renewal Course (INCLUDES Provider Manual E-Book) - 2025 Guidelines

American Heart Association

AHA BLS -Basic Life Support for Healthcare Providers Initial Certification is an instructor led four hour classroom course created by the American Heart Association to teach CPR on an Adult, Child and infant using an AED, pocket mask and bag mask. Skills taught include chest compressions and giving rescue breaths. Students watch a video and practice along with the video. At the end of the class participants will take a 25 question written test with a passing score of 84%. Students will the practice and be testing on the skills they have learned. Students who successfully complete the course will receive an American Heart Association Basic Life Support provider certification good for 2 years.

Please be sure to download all the documents required for class. There is an agenda, skills check off sheets and your E-book, Algorithms and more!

American Heart Association BLS or Basic Life Support For Healthcare Providers Initial Certification training classes at Saving American Hearts 1301 S. 8th Street Suite 116 Colorado Springs, Colorado 80905.

This 2025 AHA Basic Life Support Course trains participants to promptly recognize several life-threatening emergencies, give high-quality chest compressions, deliver appropriate ventilations and provide early use of an AED. The course reflects science and education from the American Heart Association's 2025 Guidelines Update for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC). This course is designed for Healthcare Professionals and other personnel who need to know how to perform CPR and other basic cardiovascular life support skills in a wide variety of in-hospital and out of hospital settings.

Basic Life Support is a life saving certification class that teaches how to perform CPR or Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation by providing chest compressions combined with rescue breaths. It also teaches how to use an AED or automatic external defibrillator and a bag mask device. Training is provided for Adults, Child and infants. Choking is included in the course.

Basic Life Support is the foundation for saving lives after cardiac arrest. You will learn the skills of high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for victims of all ages and will practice delivery of these skills both as a single rescuer and as a member of a multi-rescuer team. The skills you learn in this course will enable you to recognize cardiac arrest, activate the emergency response system early, and respond quickly and confidently.

Despite important advances in prevention, sudden cardiac arrest remains a leading cause of death in the Unites States. Seventy percent of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests occur in the home. About half are unwitnessed. Outcome from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest remains poor. Only about 10% of adult patients with non-traumatic cardiac arrest who are treated by emergency medical services (EMS) survive to hospital discharge.

With the knowledge and skills you learn in this course, your actions can give victims the best chance of survival.

The BLS Course focuses on what rescuers need to know to perform high-quality CPR in a wide variety of settings. You will also learn how to respond to choking emergencies.

After successfully completing the BLS Course, you should be able to

*Describe the importance of high-quality CPR and its impact on survival

*Describe all of the steps of the Chain of Survival

*Apply the BLS Concepts of the Chain of Survival

*Recognize the signs of someone needing CPR

*Perform high-quality CPR for an adult

* Describe the importance of early use of an AED

*Demonstrate the appropriate use of an AED

*Provide effective ventilations by using a barrier device

*Perform high quality CPR for a child

*Perform high quality CPR for an infant

*Describe the importance of teams in multi-rescuer resuscitation

*Perform as an effective team member during multir-escuer CPR

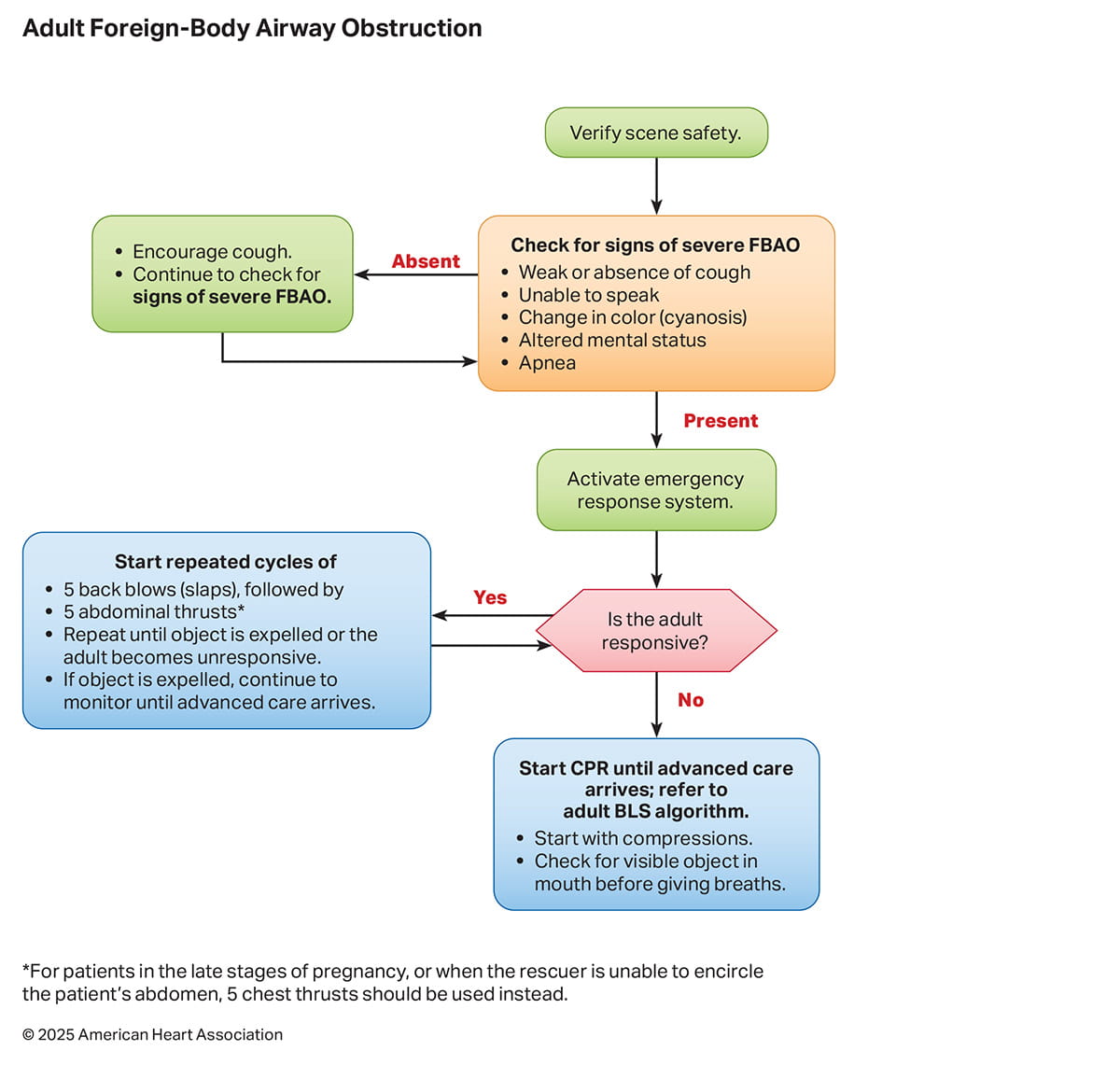

*Describe the technique for relief of foreign-body airway obstruction for an adult or child

*Describe the technique for relief of foreign-body airway obstruction for an infant

The BLS Course focuses on preparing students to perform CPR skills. CPR is a life saving procedure for a victim who has signs of cardiac arrest (unresponsive, no normal breathing, and no pulse). Components of CPR are chest compressions and breaths.

High-quality CPR improves a victim's chances of survival. Study and practice the characteristics of high-quality CPR so that you can perform each skill effectively.

High-Quality CPR

Start compressions within 10 seconds of recognition of cardiac arrest.

Push hard, push fast: Compress at a rate of 1-- to 120/min with a depth of

-At least 2 inches or 5 centimeters for adults

-At least one third the depth of the chest, about 2 inches or 5 cm for children

At least one third the depth of the chest, about 1 1/2 inches or 4 cm for infants

Allow complete chest recoil after each compression.

Minimize interruptions in compressions (try to limit interruptions to less than 10 seconds).

Give effective breaths that make the chest rise.

Avoid excessive ventilation.

Chest Compression Depth

Chest compressions are more often too shallow than too deep. However, research suggests that compression depth greater than 2.4 inches (6cm) in adults may cause injuries. If you have a CPR quality feedback device, it is optimal to target your compression depth from 2 to 2.4 inches (5 to 6 cm).

The BLS techniques and sequences presented during the course offer 1 approach to a resuscitation attempt. Every situation is unique. Your response will be determined by

-Available emergency equipment

-Availability of trained rescuers

-Level of training expertise

-Local protocols

Personal Protective Equipment

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is equipment worn to help protect the rescuer from health or safety risks. PPE will vary based on situations and protocols. It can include a combination of items such as

-Medical gloves

-Eye protection

-Full body coverage

-High-visibility clothing

-Safety footwear

-Safety helmets

Always consult with your local health authority or regulatory body on specific PPE protocols relevant to your role.

Life is Why

High-Quality CPR is Why

Early recognition and CPR are crucial for survival from cardiac arrest. Be learning high-quality CPR, you'll have the ability to improve patient outcomes and save more lives.

The Chain of Survival

At the end of this part, you will be able to

-Describe the importance of high-quality CPR and its impact on survival

-Describe all of the steps of the Chain of Survival

-Apply the BLS concepts of the Chain of Survival

Adult Chain of Survival

The AHA has adopted, supported, and helped develop the concept of emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) systems for many years. The term Chain of Survival provides a useful metaphor for the elements of the ECC systems-of=care concept.

Cardiac arrest can happen anywhere - on the street, at home, or in a hospital emergency department, intensive care unit (ICU) or inpatient bed. The system of care is different depending on whether the patient has an arrest inside or outside of the hospital.

The 2 distinct adult Chains of Survival which reflect the setting as well as the availability of rescuers and resources are:

-In-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA)

-Out-Of-Hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA)

Chain of Survival for an In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

For adult patients who are in the hospital, cardiac arrest usually happens as a result of serious respiratory or circulatory conditions that get worse. Many of these arrests can be predicted adn prevented by carful observation, prevention, and early treatment of prearrest conditions. Once a primary provider recognizes cardiac arrest, immediate activation of the resuscitation team, early high-quality CPR, and rapid defibrillation are essential. Patients depend on the smooth interaction of the institution's various departments and services and on a multidisciplinary team of professional providers, including physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, and others.

After return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), all cardiac arrest victims receive post-cardiac arrest care. This level of care is provided by a team of multidisciplinary specialists and may occur in the cardiac catheterization suite and/or ICU. A cardiac catheterization suite or laboratory (sometimes referred to as a "cath lab") is a group of procedure rooms in a hospital or clinic where specialized equipment is used to evaluate the heart and the blood vessels around the heart and in the lungs. A cardiac catheterization procedure involves insertion of a catheter through an artery or vein into the heart to study the heart and its surrounding structures and function. Measurements are made through the catheter, and contrast material may be used to create images that will help identify problems. During the procedure, specialized catheter can be used to fix some cardiac problems (such as opening a blocked artery).

The links in the Chain of Survival for an adult who has a cardiac arrest in the hospital are

-Surveillance, prevention, and treatment of prearrest conditions

-Immediate recognition of cardiac arrest and activation of the emergency response system

-Early CPR with an emphasis on chest compressions

-Rapid defibrillation

-Multidisciplinary post-

Chain of Survival for an Out-Of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

Most out-of-hospital adult cardiac arrests happen unexpectedly and result from underlying cardiac problems. Successful outcome depends on early bystander CPR and rapid defibrillation in the first few minutes after the arrest. Organized community programs that prepare the lay public to respond quickly to a cardiac arrest are critical to improving outcome from OHCA.

Lay rescuers are expected to recognize the victim's distress, call for help, start CPR, and initiate public-access defibrillation until EMS arrives. EMS providers then take over resuscitation efforts. Advanced care, such as administration of medications, may be provided. EMS providers transport the cardiac arrest victim to an emergency department or cardiac catheterization suite. Follow-up care by a team of multidisciplinary specialists continues in the ICU.

The links in the Chain of Survival for an adult who has a cardiac arrest outside the hospital are

-Immediate recognition of cardiac arrest and activation of the emergency response system

- Early CPR with an emphasis on chest compressions

-Rapid defibrillation with an AED

-Effective advanced life support (including rapid stabilization and transport to post-cardiac arrest care)

-Multidisciplinary post-cardiac arrest care

Pediatric Chain of Survival

In adults, cardiac arrest is often sudden and results from a cardiac cause. In children, cardiac arrest is often secondary to respiratory failure and shock. Identifying children with these problems is essential to reduce the likelihood of pediatric cardiac arrest and maximize survival and recovery. Therefore, a prevention link is added in the pediatric Chain of Survival

-Prevention of arrest

-Early high-quality bystander CPR

-Rapid activation of the emergency response system

-Effective advanced life support (including rapid stabilization and transport to post cardiac arrest care)

-Integrated post-cardiac arrest care

Cardiac Arrest or Heart Attack?

People often use the terms cardiac arrest and heart attack interchangeably, but they are not the same.

Sudden cardiac arrest occurs when the heart develops an abnormal rhythm and can't pump blood

A heart attack occurs when blood flow to part of the heart muscle is blocked.

High-Performance Rescue Teams

Coordinated efforts by several rescuers during CPR may increase chances for a successful resuscitation. High performance teams divide tasks among team members during a resuscitation attempt. As a team member, you will want to perform high-quality CPR skills to make your maximum contribution to each resuscitation team effort.

Main Components of CPR

CPR consists of these main components

-Chest Compressions

-Airway

-Breathing

Adult 1 -Rescuer BLS Sequence

IF the rescuer is alone and encounters an unresponsive adult, follow these steps

Step 1 - Verify that the scene is safe for you and the victim. You do not want to become a victim yourself

Step 2 - Check for responsiveness. Tap the victim's shoulder and shout. "Are you ok?"

Step 3 - If the victim is not responsive, shout for nearby help

Step 4 - Activate the emergency response system as appropriate in your setting. Depending on your work situation, call 9-1-1 from your phone, mobilize the code team, or notify advanced life support.

Step 5 - If you are alone, get the AED/defibrillator and emergency equipment. If someone else is available, send that person to get it.

Next, assess the victim for normal breathing and a pulse. This will help you determine appropriate actions.

To minimize delay in starting CPR, you may assess breathing at the same time as you check the pulse. This should take no more than 10 seconds.

Breathing

To check for breathing, scan the victim's chest for rise and fall for no more than 10 seconds.

-If the victim is breathing, monitor the victim until additional help arrives.

-If the victim is not breathing or is only gasping, this is not considered normal breathing and is a sign of cardiac arrest.

Agonal Gasps

Agonal gasps are not normal breathing. Agonal gasps may be present in the first minutes after sudden cardiac arrest.

A person who gasps usually looks like hi is drawing air in very quickly. The mouth may be open and the jaw, head, or neck may move with gasps. Gasps may appear forceful or weak. Some time may pass between gasps because they usually happen at a slow rate. The gasp may sound like a snort, snore, or groan. Gasping is not normal breathing. It is a sign of cardiac arrest.

Check Pulse

To perform a pulse chick in an adult, palpate a carotid pulse

First, locate the trachea, on the side of the neck closest to you. Slide these 2 or 3 fingers into the groove between the trachea and the muscles at the side of the neck, where you can feel the carotid pulse. Feel for a pulse for at least 5 seconds, but not more than 10.

IF you do not definitely feel a pulse within 1- seconds, begin high-quality CPR, starting with chest compressions. In all scenarios, by the time cardiac arrest is identified, the emergency response system or backup must be activated, and someone must be sent to retrieve the AED and emergency equipment.

If the victim is not breathing normally or is only gasping and has no pulse, immediately begin high-quality CPR, starting with chest compressions. Remove or move the clothing covering the victim's chest so that you can locate appropriate hand placement for compressions. This will also allow placement of the AED pads when the AED arrives.

After 30 compressions have been performed, use the head tilt, chin lift and give 2 rescue breaths while watching for chest rise and immediately resume chest compressions. Perform 30 compressions and 2 breaths for five cycles and recheck for a pulse. If there is still no pulse, resume chest compressions and breaths until help arrives, or until you are physically not able to continue. No one expects you to be able to continue CPR forever. You will eventually become exhausted and unable to continue.

Defibrillation

Attempt Defibrillation Use the AED as soon as it is available, and follow the prompts

External Defibrillator for Adults and Children 8 Years of Age and Older

Resume High-Quality CPR

Immediately resume high-quality CPR, starting with chest compressions, when advised by the AED. Continue to provide CPR, and follow the AED prompts until advanced life support is available.

Importance of Chest Compressions

Each time you stop chest compressions, the blood flow to the heart and brain decreases significantly. Once you resume compressions, it takes several compressions to increase blood flow to the heart and brain back to the levels present before the interruption. Thus, the more often chest compressions are interrupted and the longer the interruptions are, the lower the blood supply to the heart and brain is.

High-Quality Chest Compressions

If the victim is not breathing normally or is only gasping and has no pulse, begin CPR, starting with chest compressions.

Single rescuers should use the compression-to-ventilation ratio of 30 compressions to 2 breaths when giving CPR to victims of any age.

When you give chest compressions, it is important to

Caution

Do Not Move the Victim During Compressions

Do not move the victim while CPR is in progress unless the victim is in a dangerous environment (such as a burning building) or if you believe you cannot perform CPR effectively in the victim's present position or location.

When help arrives, the resuscitation team, based on local protocol, may choose to continue CPR at the scene or transport the victim to an appropriate facility while continuing rescue efforts.

Foundational Facts

The Importance of a Firm Surface

Compressions pump the blood in the heart to the rest of the body. To make compressions as effective as possible, place the victim on a firm surface, such as the floor or a backboard. If the victim is on a soft surface, such as a mattress, the force used to compress the chest will simply push the body into the soft surface. A firm surface allows compression of the chest and heart to create blood flow.

Chest Compression Technique

Compressions in an adult:

Position yourself at the victim's side.

Make sure the victim is lying face up. on a firm flat surface. If the victim is lying face down, carefully roll him to a faceup position.

Position your hands and body to perform chest compressions:

• Put the heel of one hand in the center, of the victim's chest, on the lower half of the breastbone (sternum).

• Put the heel of your other hand on top of the first hand.

• Straighten your arms and position your shoulders directly over your hands

Give chest compressions at a rate of 100 to 120/min.

Press down at least 2 inches (5 cm) with each compression (this requires her Work). For each chest compression, make sure you push straight down on the victim's breastbone (Figure 8B).

At the end of each compression, make sure you allow the chest to recoil complete, Minimize interruptions of chest compressions (you will learn to combine compressions with ventilation next).

Chest Recoil

Chest recoil allows blood to flow into the heart. Incomplete chest recoil reduces the fling of the heart between compressions and reduces the blood flow created by chest compressions. Chest compression and chest recoil/relaxation times should be about equal.

Technique for Chest Compressions

If you have difficulty pushing deeply during compressions, put one hand on the breastbone to push on the chest. Grasp the wrist of that hand with your other hand to support the first hand as it pushes the chest.

See our live calendar of classes here:

https://www.keepandshare.com/calendar/show.php?i=2091851&vw=month&ign=y

If you have a current AHA BLS card and just need a renewal, you can also visit

https://savingamericanhearts.com/aha-bls-renewal/

And, if you want to take the online course at www.elearning.heart.org you can do the online course and then just come in for the in-person hands on practice and testing session. There are two separate fees, and this is the most expensive way to go, so do a little research first. The classroom courses are much cheaper.

Here's our class dates for the BLS Skills Sessions

https://savingamericanhearts.com/aha-bls-skills-session/

Here's a link to our calendar: https://www.keepandshare.com/

and to our Refund Policy: https://savingamericanhearts.com/refund-policy/

These guidelines are used to help people who are experiencing cardiac arrest, respiratory distress, or an obstructed airway. Basic life support is a level of medical care which is used for patients with life-threatening condition of cardiac arrest until they can be given full medical care by advanced life support providers.

BLS training reinforces healthcare professionals’ understanding of the importance of early CPR and defibrillation, performing CPR, choking relief, using an AED, and the role of each link in the Chain of Survival. BLS is performed to support the patient's circulation and respiration through the use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

In this course you will learn:

• High-quality BLS for adults, children, and infants

• Use of an AED

• Effective ventilation using a barrier device

• Relief of foreign-body airway obstruction for adults, children, and infants

• High-performance teams

CPR Coach

The CPR Coach is a new role within the resuscitation team. The CPR Coach role is designed to promote the delivery of high-quality CPR and allow the Team Leader to focus on other elements of cardiac arrest care, coordinate the various team members’ assigned tasks, and ensure that clinical care is delivered according to AHA guidelines.

The AHA has adopted an open-resource policy for exams. Open resource means that students may use resources as a reference while completing the exam. Resources could include the provider manual, either in printed form or as an eBook on personal devices, any notes the student took during the provider course, the 2025 Handbook of ECC for Healthcare Providers, the AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC, posters, etc. Open resource does not mean open discussion with other students or the Instructor. Students may not interact with each other during the exam.

To successfully complete this course and receive your BLS course completion card, students must do

the following:

• Participate in hands-on interactive demonstrations of high-quality CPR skills

• Pass the Adult CPR and AED Skills Test

• Pass the Infant CPR Skills Test

• Score at least 84% on the exam

Upon completion of the course, students will receive an American Heart Association BLS Provider Card valid for two years. Once you receive your card, be sure to set an alarm on your phone for 23 months from now. That way you’ll have 30 days to find and attend a class before your expiration date. Your card is good until midnight on the last day of the month.

Continuing Education Accreditation – Emergency Medical Services This continuing education activity is approved by the American Heart Association, an organization accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Pre-Hospital Continuing Education (CAPCE), for 3.25 Educator CEHs, activity number 20-AMHA-F2-0083.

The American Heart Association’s 2025 Adult Basic Life Support Guidelines

The American Heart Association’s 2025 Adult Basic Life Support Guidelines build upon prior versions with updated recommendations for assessment and management of persons with cardiac arrest, as well as respiratory arrest and foreign-body airway obstruction. The chapter addresses the important elements of adult basic life support including initial recognition of cardiac arrest, activation of emergency response, provision of high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and use of an automated external defibrillator. In addition, there are updated recommendations on the treatment of foreign-body airway obstruction. The use of opioid antagonists (eg, naloxone) during respiratory or cardiac arrest is incorporated into the adult basic life support algorithms, with more detailed information provided in “Part 10: Adult and Pediatric Special Circumstances of Resuscitation.”

The annual incidence of adults treated by emergency medical services (EMS) for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in the United States varies considerably between states, but is estimated at 356 000, or 83 per 100 000 populations.1,2 Despite advances in public education and awareness, as well as improvement in community-based systems of care, survival for adults after OHCA remains low and decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 The Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES) is a voluntary OHCA database used by EMS agencies and hospitals to generate Utstein-style reports and to benchmark performance and outcomes against similar systems. Developed in 2004, CARES now has participating sites from 37 states covering approximately 56% of the US population. CARES OHCA data from 2024 showed that survival to hospital discharge was 10.5%, with favorable neurologic outcome reported in approximately 8.2%.4 The majority of adult OHCA occurred in private residences while 18% occurred in public places. Bystander CPR was provided in 47.7% of adult OHCA, and a bystander used an automated external defibrillator (AED) in 7.9% of cases. There is significant variation in rates of bystander CPR, public AED use, EMS response times, and survival from cardiac arrest between geographic regions, as well as disparities associated with race, sex, and socioeconomic status.5,6

The annual incidence of adult in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) in the United States is estimated to be 292 000 by extrapolation from the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation registry.7 Approximately 60% of adult IHCA occur in an acute care setting (eg, intensive care unit, emergency department, operating room) while 40% occur on the general inpatient units. Survival to hospital discharge decreased from 26.7% to a low of 18.8% during the COVID-19 pandemic, with improvement to 23.6% in 2023.1 Racial and sex-related outcome disparities have also been observed in the IHCA setting.8,9

Early, high-quality CPR and prompt defibrillation are the most important interventions associated with improved outcomes in adult cardiac arrest. Despite this, a 2015 US prevalence report found that only 18% of people surveyed had current CPR training,10 with lower rates in under-represented and low-income populations. More lives could be saved if a greater proportion of the public was trained in, and willing to perform, basic life support, especially chest compressions.11

Since 2010, the American Heart Association (AHA) Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) Committee has regularly set goals aimed at increasing survival from cardiac arrest. The accompanying strategies focus on strengthening the links in the Chain of Survival to prevent, identify, treat, and support all phases of care for persons who are at risk for, or experience, cardiac arrest. The fundamental basic life support tasks of recognition of cardiac arrest, activation of emergency response, performance of chest compressions and ventilations, and use of an AED for defibrillation are critical components representing the first links of the Chain of Survival that must be optimized so persons with cardiac arrest can fully benefit from advanced cardiovascular care therapies.12

The 2030 Impact Goals focus on improving survival to hospital discharge with favorable neurologic outcome for individuals experiencing OHCA or IHCA.13 Not surprisingly, the first 2 goals are related to basic life support: bystander CPR and public access defibrillation. Specifically, the first goal calls for an increase in bystander adult CPR performance rates to greater than 50%, while the second goal is to increase the proportion of adults with cardiac arrest for whom an AED is applied before emergency medical response arrival to greater than 20%. To accomplish these goals, the evidence-based recommendations for performance of high-quality basic life support provided in this chapter must be coupled with strategies for awareness, advocacy, and education that improve the system of care for all persons. The accompanying chapters “Part 12: Resuscitation Education Science” and “Part 4: Systems of Care” provide recommendations for optimizing the community and health care system approach to cardiac arrest treatment, including bystander CPR training, telecommunicator CPR, public access defibrillation, and timely activation of the emergency medical response system. While all components of the Chain of Survival are essential, high-quality basic life support is foundational to improving outcomes.

These recommendations supersede the last full set of AHA Guidelines for Adult Basic Life Support published in 202014 unless otherwise specified. The writing group reviewed all relevant and current AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC and all relevant International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus on CPR and ECC science with treatment recommendations from 2020 through 2024.15-18 Evidence and recommendations were reviewed to determine if current guidelines should be reaffirmed, revised, or retired, or if new recommendations were needed. The writing group then drafted, reviewed, and approved each recommendation. For topics that did not undergo full evidence review or updated literature search, the recommendations, recommendation-specific supportive text, and references from the 2020 Basic Life Support Guidelines were not updated and were carried over. These topics are noted within the synopsis of their respective sections and remain as the current guidelines for 2025.

The 2025 Adult Basic Life Support Guidelines apply to a range of responders, including trained and untrained lay rescuers and health care professionals, with the understanding that systems of prehospital and in-hospital care vary widely across the world. They address the treatment of cardiac arrest as well as other immediately life-threatening conditions including respiratory arrest and FBAO. A person in cardiac arrest who has signs of puberty is treated by using the Adult Basic Life Support Guidelines; guidelines for pediatric patients are discussed in “Part 6: Pediatric Basic Life Support.”

Three algorithms are included in the 2025 Guidelines as resources. The Adult Basic Life Support for Health Care Professionals Algorithm (Figure 1) now incorporates the use of opioid antagonists for both respiratory and cardiac arrest. A new adult basic life support algorithm (Figure 2) illustrates the approach for lay rescuers. A new algorithm for assessment and treatment of FBAO (Figure 3) is also provided.

The first link in the Chain of Survival for cardiac arrest includes prompt activation of the emergency response system. Given that most lay rescuers will likely have mobile phones with hands-free options, it is possible for lay rescuers to provide CPR and activate the emergency response system at nearly the same time. Alternatively, a second lay rescuer can be instructed to call 911. Activation of the emergency response system allows for provision of telecommunicator CPR, possible notification of other lay rescuers via crowd-sourced applications, and dispatch of the designated EMS agency.

Immediate chest compressions are critical to improve patient outcomes from OHCA, and a chest compression–only approach is appropriate if lay rescuers are untrained or unwilling to provide breaths. Because CPR with breaths may lead to improved outcomes for adults in comparison with chest compression–only CPR, trained rescuers are encouraged to provide breaths along with chest compressions. PPE provides an important barrier against certain infectious diseases, but lay responders may have limited access to PPE.

As health care professionals are trained to deliver compressions and ventilation, they are in a position to provide both during adult basic life support.

Opening the airway is a key component of basic life support for patients who are unresponsive with or without respiratory or cardiac arrest. Unresponsive individuals are at risk for airway obstruction primarily due to the tongue falling to the back of the oropharynx as the oropharyngeal muscles lose tone. Untreated airway obstruction can lead to hypoxia and hypercarbia, which may precipitate cardiac arrest. Alternatively, uncorrected airway obstruction may hinder resuscitation efforts. Airway adjuncts such as oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways can improve airway patency by creating a passage between the tongue and the pharynx. However, these devices have contraindications with suspected facial trauma (nasopharyngeal airway) and an intact gag reflex (oropharyngeal airway). Rescuers need to consider the possibility of cervical spine injury when there is known or suspected trauma. Cricoid pressure has not been shown to have benefit and has the potential to interfere with air entry into the trachea during bag-mask ventilation.

Figure 4 – Head Tilt-Chin Lift

Opening the airway using the head tilt–chin lift technique.

An adult with signs of head or neck trauma may have a cervical spine injury. Trained rescuers should attempt to open the airway using the jaw thrust technique because this maneuver produces less movement of the head and neck than a head tilt–chin lift. If it is not possible to achieve an open airway with a jaw thrust and insertion of an airway adjunct, trained rescuers should open the airway by using the head tilt–chin lift given the critical importance of oxygenation and ventilation. No new evidence was identified on this topic during the 2025 evidence review.

High-quality resuscitation is vital for improved cardiac arrest outcomes including return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and survival. The effectiveness of chest compression delivery can be improved through optimizing rescuer hand position, rescuer body position, and patient position.

Figure 6 – Side view of rescuer position

Side view of rescuer position and hand location for chest compressions.

Key components of high-quality CPR include minimizing interruptions, compressing at an optimal rate and depth, providing adequate chest recoil, and avoiding excessive ventilation.34,56,57 Although there are numerous retrospective observational studies, there is a paucity of prospective studies or randomized trials specifically examining CPR quality targets. Further, evidence suggests interactions between CPR components (eg, rate and depth) confound studying them in isolation. These limitations do not reduce the importance of these elements, rather they underscore the need for ongoing investigations into ideal CPR performance.

This is the most expensive way to get certified. The online course is $38 and the in person portion is $50. It's cheaper to just come to class. Renewal is three hours and Initial is 4-5 and the total cost is $50. Includes tax, certification card and your e-book!

During the skills session a BLS instructor will guide the student through a series of scenarios consisting of adult, child and infant CPR using a bag mask device and an AED.

Basic Life Support (BLS) skills testing is a live exam that assesses a student's ability to perform BLS skills they learned during certification. The test is designed to evaluate a student's knowledge and proficiency in performing essential BLS skills, such as chest compressions, rescue breathing, and automated external defibrillation (AED).

You will first practice and then be tested on 1 Rescuer Adult CPR with a bag mask and then 2 Rescuer Adult CPR with a bag mask and an AED.

Next you will practice and then be tested on 1 and 2 rescuer infant CPR with a bag mask, pocket mask and AED.

Upon successful completion of the course, students will receive a same day American Heart Association 2025 Guidelines BLS Provider Card valid for two years.

A Basic Life Support (BLS) Skills Checkoff is a hands-on evaluation by a certified instructor, verifying a learner's competence in life-saving techniques like high-quality CPR (compressions & breaths), AED use, and team dynamics for adults, children, and infants, often after completing online training, to get an official BLS certification card. It assesses critical steps, including scene safety, responsiveness checks, calling for help, proper hand placement, compression rate/depth, chest recoil, and effective rescue breaths, ensuring readiness for real emergencies.

This was a great course and resource materials were easy to understand and read.

I highly recommend the Saving American Hearts, Inc. for their Basic Life Support (BLS) / CPR and other classes, due to their responsiveness and excellent teaching. In addition the fee is less expensive, and woman owned also.

Will take it here again.

Amazing program and instructor was really helpful and nice and made the best jokes

This was the most engaging class I've had for BLS. I used this as a means of recertifying and the instructor was helpful, well informed, and knew how to keep the class enagaged and responsive.

Loved it!